History of Peron – The Rise, Fall and Lasting Legacy of Argentina’s Most Enigmatic Leaders

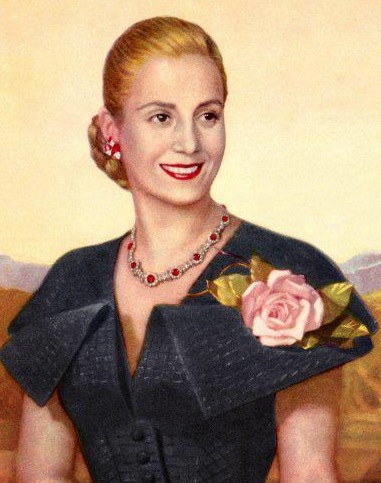

Juan Domingo Peron and his wife, Eva – more commonly known as Evita – are undoubtedly the most significant political figures in the history of Argentina. Their influence was so monumental and far-reaching that they are credited with changing the political topography of South America in general.

Even nowadays, six decades after Evita’s death and more than four of that of her husband, Peronism is still said to be one of the most powerful and prominent political philosophies in the entire continent.

The populism ideology has been rebranded, renamed, and effectively reshaped, but the ideas have remained the same. Whilst once upon a time aspiring politicians would seduce the upper classes and wealthy businessmen, they now court the commoners, the middle class, the disenfranchised and the underprivileged. Because if there’s one thing that the Perons taught South America, Evita in particular, is that the only road to political success is paved by the masses. Not with force, not with revolution, but through sheer will and popularity.

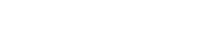

By the time Evita died of cancer at the age of 33 in 1952, she had gained a cult-like status, one that continues to exist even now, among generations of Argentinians who weren’t even alive when she was. Her rise as a ‘symbol of the people’ wasn’t just due to charisma alone. In her political life, she championed women’s rights, starting the largest women-only political party in Argentina and achieving suffrage for women in 1947.

Along with her husband, she championed the rights of workers, ones she called the ‘shirtless’ (descamisados), and aided the poor, personally handing out money to the needy. Her rise to god-like status piqued after her death. As the nation plunged into mourning, thousands wrote letters to the Pope requesting, no, demanding she be given sainthood. She was given a state funeral, something usually only afforded to heads of state.

Her husband, Juan Peron, was likewise popular. He was elected President of Argentina twice before being deposed in a military coup and being sent to Spain in exile. Peron would spend 18 years away from his country before returning in 1973. When the plane he was flying in landed in Buenos Aires, over 3 million people greeted him at the arrival’s gate.

Support for the man credited with modernising Argentina had not waned, in all that time. Peron died a year after returning to Argentina, but not before winning yet another election and rising to the Presidential seat for the third time.

Yet for every champion there are retractors. In the case of Juan and Evita Peron, lots of them. What some saw as charisma, others deemed theatrics. The Perons have, since the time they rose to prominence, been accused of calculating everything they did and said. Critics accused them of being demagogues, of inciting and seducing the masses by eliciting anger and fear. Both were fiercely criticised for their inability to accept personal criticism.

Vocal retractors were accused of being unpatriotic and routinely jailed. Whilst some view the Perons as champions of the people others see them as authoritarian dictators. Juan’s admiration for Benito Mussolini and his ideals have long since been documented.

The Peron’s political ambivalence, the precise base of Peronism, would go on to define their rule. Juan Peron managed to maintain friendly relation with both the US and Russia during the Cold War and, after WWII, granted refuge to boatloads of Holocaust survivors and former Nazis escaping justice in Europe.

Argentina boasted one of the largest Jewish populations before WWII and, thanks to Juan Peron’s welcoming and sympathetic spirit, boasts nowadays the largest population of Jews in Latina America.

The Peronist movement, and its three-flag ideology of political sovereignty, economic independence and social justice, has come under great scrutiny since its inception. Yet it should be noted that the great majority of criticism at the time was directed at Juan Peron. In the eyes of her admirers, and there were and still are a great many, Evita could simply do no wrong.

From modest beginnings…

Peron was born into a modest middle-class family in 1895. He forged a career in the military where he had risen to the rank of colonel before spearheading a military overthrow of Argentina’s civilian government in 1943. Known to be a shrewd and calculating player, many describing him as the ultimate demagogue, Peron granted himself the very modest title of Secretary of Labour at first.

He introduced numerous reforms aimed at improving working conditions, winning him support and loyalty of labour unions, attributes he would come to rely upon to build a very powerful political empire.

Evita, on the other hand, had a much more modest start in life, which would turn out to be pivotal in her rise to immense popularity. The illegitimate child of a poor peasant woman, she determined to use her beauty and charm to forge an acting career and crawl out of her disadvantaged life. Her glamorous image was like an oasis to poorer Argentinians, especially women of course, who took it as proof that it was possible to rise from the rubbles of a meagre start to improve one’s standing in society.

She became a real-life Cinderella on the arms of her powerful husband, and expertly carved an indispensable role for herself. As the wife of the President, she has a tremendously effective platform with which to work. She elicited not just support but love and devotion by appealing to the masses and professing her empathy to their plight. Yet her lack of official status or office meant she easily dodged criticism. Evita became untouchable and her untimely death meant she would continue to be remembered this way.

Historians believe that the myth of Evita was created solely by the fact that she died so young. Her proponents will forever decry the injustice of an Argentina without Evita as President, yet political analysts believe her downfall would have been inevitable.

With no qualifications and no expertise in the gutter-world of politics and diplomacy, many feel that most – if not all – of her promises to the people would have gone unfulfilled anyhow. Eventually, they say, the masses would have been disappointed and their devotion would have been eroded.

Peron as President

By the time Peron was elected President of Argentina in 1946 he was ready to make some serious changes to his country’s administration. He introduced radical social reforms, nationalised railways and banks, raised wages and limited working hours, introducing obligatory Sundays off for most jobs. He took on a colossal amount of public building, constructing schools and hospitals, and consolidating his (and his wife’s) continued adoration by the working class.

The death of Evita signalled, in hindsight, a dramatic change in Peron’s leadership and popularity. Coinciding with the stagnation of the country’s economy, and increasing distrust of Peron by conservatives, his support began to wane. Rumours of improper behaviour with young Peronist female followers marred his reputation and turned once-adoring women against him. He fell foul with the Catholic Church in Argentina, then (and still now) a formidable force in the country.

He was excommunicated after trying to legalize prostitution and divorce, and his military opposers took advantage of the situation to launch a violent coup, which included bombing of Plaza De Mayo by the Air Force, resulting in the death of over 400 people. In September 1955, Peron was narrowly evacuated from his office as the military took hold in Cordoba. Peron would spend the next 18 years in exile, first in Venezuela and Panama before eventually settling in Spain.

Peron in exile

The fact that the Peronist movement continued to grow and thrive in Argentina even during Peron’s exile, and considering that even uttering his name in public was made illegal, is testament to the indescribable power both Juan and Evita achieved.

The ever-skilful diplomat, Peron continued to receive visits from prominent politicians in his home in Spain, and quite a few of his faithful followers won elections back home on a recurring basis.

By the time the 1973 elections took place, it was widely believed that the Peronist candidate, Hector Campora, was simply a stand-in for Peron. Once a win was secured, Peron was given the go-ahead to return, and an estimated 3 million Argentinians greeted his return at the airport in Buenos Aires. Peron replaced Campora for his third, and final, term as President of Argentina, but died of a heart-attack a year from his return.

Ultimately, perhaps, proving that behind a great man needs to stand a great woman, it seems that Peron’s next choice of wife would turn out to be his biggest undoing. There’s no doubt that Isabel Peron had big shoes to fill, yet her unpopularity and incompetence – especially after the death of her husband – signalled the end of majority support for Peron.

Although she did manage to take the leadership and hold on to it for a year and a half, Isabel Peron was eventually deposed in a military coup in 1976, an event which plunged Argentina into a brutal dictatorship that would continue until 1982.

The legacy of Peron

In a continent renowned for idolising its leaders and fighters, Juan and Evita Peron stand apart. They rose to prominence at a time when Argentina needed to hope and dream most. For the first time in the country’s history, the spotlight was firmly set on the working class and the welfare programs, financial independence and sovereignty Peron created would serve to create a lasting legacy, one that still exists today. Not only in Argentina, but throughout all of South America.

The history and culture of Argentina makes it an immensely rewarding country to visit. So take a look at our extensive collection of Argentina tours and come discover South America with Chimu Adventures.

Where Will You Go Next ?

- Popular Destinations

- Antarctica

- The Arctic

- South America

- Central America

- More to explore

- Amazon

- Antarctic Circle

- Antarctic Peninsula

- Argentina

- Bolivia

- Brazil

- Canadian Arctic

- Chile

- Colombia

- Costa Rica & Panama

- East Antarctica

- Ecuador

- Galapagos Islands

- Greenland

- Guatemala & Honduras

- Machu Picchu

- Mexico

- Patagonia

- Peru

- South Georgia and Falkland Islands

- Spitsbergen

- Sub Antarctic Islands

Talk to one of our experienced Destination Specialists to turn your Antarctic, Arctic and South American dream into a reality.

Contact us