The History of Antarctica – A Story of Great Explorers

Who first saw Antarctic ice and who first discovered Antarctica? Europeans are used to putting a person’s name to such things, such as “Christopher Columbus discovered America” (he didn’t, actually), but the discoverers of Antarctica could well be nameless individuals from the Pacific. Here’s everything you need to know about the history of Antarctica!

The History of Antarctica

We know the Polynesian people were superb navigators and explored far southern waters. Pacific oral history tells of a canoe voyage around AD 650 reaching Antarctic sea ice. It’s even possible, though unlikely, that an open ice pack during a balmy late summer permitted Polynesians to see and even land on the Antarctic mainland.

European Discoverers

The history of Antarctica starts off with the European discoverers. Nearly 1000 years later, Europeans reached Antarctic waters. In 1599, Dutchman Dirck Gerritsz described land in the vicinity of the South Shetland Islands, and through the 1600s Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, English and French navigators penetrated south of Cape Horn. The Englishman Antonio de la Roché reached South Georgia in the far South Atlantic in 1675, and around the same time other voyagers described “ice islands” south of South America.

The Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Charles Bouvet de Lozier (Bouvet) discovered the remote island that bears his name in 1739, and in 1762 the Spaniard Joseph de la Llana charted rocks west of South Georgia now called Shag Rocks. More French voyages quickly followed. Kerguelen Island was discovered in the southern Indian Ocean by an expedition under Yves Joseph de Kerguelen, and Marion de Fresne’s expedition discovered two island groups, now known as Prince Edward and Crozet, south-east of Africa.

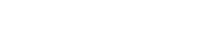

James Cook

James Cook has a central place in the history of Antarctica. His circumnavigation of Antarctica from 1772 to 1775 was the first of many government-instigated expeditions to the Antarctic. Cook did not sight land, but his two ships penetrated well into the sea ice and well south of the Antarctic Circle, far enough that he was able to say with reasonable confidence that there was land over the South Pole.

Cook’s published account of his discoveries, including descriptions of large numbers of whales and seals in the Southern Ocean, sparked a gold rush of sorts. With a constant high demand for oil from marine animals, from the late 1770s large numbers of European and North American private voyages brought back lucrative cargoes of oil from whales and seals, as well as the pelts of fur seals, from Antarctic and subantarctic seas and islands.

Sealers Discovered Antarctica

Sealers played a big role in the history of Antarctica. They have been seeking new hunting grounds with intact seal colonies were eager explorers but not inclined to share any new discoveries, so news of new lands was sometimes held back for years.

An exception was the London-based Enderby Brothers, responsible for significant discoveries in the Southern Ocean from 1775 to the early-1850s, including Auckland Islands (now a New Zealand territory) in 1805. In 1810 Frederick Hasselburg, a sealer operating out of Sydney, discovered Macquarie Island. Nine years later an English sealer, William Smith, confirmed the existence of the South Shetland Islands off the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, and in November 1820 a US sealer, Nathanial Palmer, may have been the first captain to sight the Antarctic mainland.

The financial success and notorious behaviour of unregulated sealer gangs sparked a growing public interest in southern parts, which in turn drew governments into the mix. Half a century after Cook’s voyage, the next national expedition was organised by the Russian navy under the command of one of its captains, Estonian-born Thaddeus von Bellingshausen. Like Cook he circumnavigated the continent, penetrating south of the Antarctic Circle six times, discovering Peter I and Alexander Islands. If Palmer’s sighting of Antarctica wasn’t genuine (and there are doubts about his claim), then Bellingshausen almost certainly deserves that prize, in January 1821.

In the early 1820s, tens of thousands, perhaps millions, of Antarctic seals were slaughtered, mainly for their oil and fur. But commercial ventures also made many discoveries. Records are unclear, but a party from a US sealing vessel commanded by John Davis probably made the first landing on the Antarctic continent, at Hughes Bay on the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula, in February 1821. In 1823 London-based James Weddell led the most famous of all sealing voyages deep into the sea named after him, attaining a “farthest south” record that was not beaten for nearly a century.

Two epic Enderby Brothers voyages exploring East Antarctica were led by John Biscoe in 1831 and by John Balleny in 1839. If Davis’s crew didn’t land in 1821, a New York-based whaler named Mercator Cooper led the first Antarctic landing, on the Ross Sea coast in 1853, and it was a US sealer, Erasmus Rogers, who made the first landing on Heard Island in 1855.

Ship-based National Exploration

The high point of ship-based national exploration was around 1840, when France, the United States and Great Britain each dispatched Antarctic expeditions. Frenchman Jules-Sebastien-Cesar Dumont d’Urville was first, exploring the Antarctic Peninsula in 1838 and the Antarctic coast south of Hobart (naming Adélie Land after his wife) in 1840. Charles Wilkes led the first “United States Exploring Expedition” to the Antarctic Peninsula a year after Dumont d’Urville, then undertook an extensive voyage along the coast of Antarctica south and south-west of Hobart.

Royal Navy captain James Clark Ross had already had experience in Arctic ice when he was put in command of a party that left England in 1839. His most important discoveries were Antarctica’s largest coastal sea and its largest ice shelf, which were both named in his honour. He also discovered the Transantarctic Mountains and the active volcano of Mt Erebus, before completing an Antarctic circumnavigation in 1843.

Whalers came into the story

The decimation of seal populations saw a focus from the mid-1850s on deep-sea whaling, a trade that saw the Scandinavians enter the Antarctic story for the first time. Norwegian whalers Carl Larsen, Henryk Bull and Carsten Borchgrevink are remembered by posterity not for catching whales but exploring Antarctic waters and, in Borchgrevink’s case, by becoming the first to spend winter ashore in Antarctica in 1899, at Cape Adare south of New Zealand.

“Heroic Age” of Antarctic Exploration

An expedition under the Belgian Adrien de Gerlache spent the 1898 winter beset in sea ice south-west of South America and escaped the ice by a hair’s breadth near the end of a second summer. Thus began what became known as the “heroic age” of Antarctic exploration, peppered with people who made the journey south for honour and glory rather than money. It marks a significant shift from sea exploration to land-based parties, notably those expeditions whose main aim was to be first to reach the South Pole.

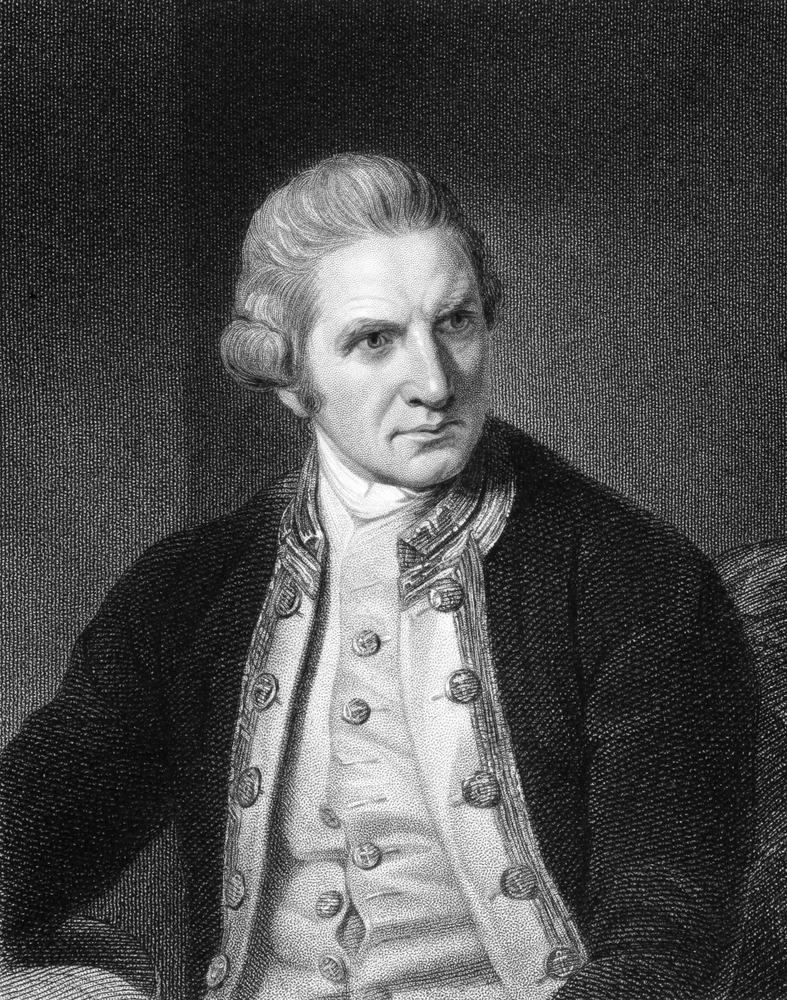

Englishman Robert Scott was the first to put up his hand in the race to the Pole, and the most famous. But it was the Norwegian Roald Amundsen who was the success story – in 1912 he won the glittering prize. He beat Scott to the Pole by a few weeks, and then unlike Scott got back alive to tell his story. Looking over Scott’s shoulder was Ernest Shackleton, an Irishman who didn’t make the Pole but won global fame by a truly heroic feat of leadership: an epic journey out of the Weddell Sea to South Georgia after his ship was crushed by pack ice.

There were many others. Erich von Drygalski brought his homeland, Germany, into Antarctic exploration. Beset in ice, he was forced to spend winter off the coast of East Antarctica in 1902. Otto Nordenskjold led a Swedish expedition that finished up with an Antarctic story as epic as any: the mother ship lost in ice, a divided expedition with parties surviving a winter in three separate places, and a lucky rescue helped by a warm spring. A Scottish expedition under William Bruce discovered Coats Land in the Weddell Sea before wintering in the South Orkneys.

Science had a place in most of these expeditions. Drygalski, Nordenskjold and Bruce – all scientists – gave research the highest priority in their plans. But the prize for the most productive scientific expedition of the heroic era goes to the Australian, Douglas Mawson, probably the most known name within the history of Antarctica. His Australasian Antarctic Expedition was a bigger, more ambitious and more successful scientific endeavour than any of its contemporaries. Mawson kept away from the race to the Pole because he believed good science was a better path to national glory, and the result was an unrivalled legacy of published science.

Nationalism featured in the big expeditions of the inter-war years – in Mawson’s second expedition along the East Antarctic coast, in the Norwegian whaler Lars Christensen’s circumnavigation, in Lincoln Ellsworth’s aerial exploration of West Antarctica and in US naval commander Richard Byrd’s epic Ross Sea expeditions. Byrd, who knew a lot about publicity in an age of radio and cinema, also became something of a national hero in his own right. Even Hitler’s Germany became involved, dropping Nazi swastikas from ship-based aircraft to claim a slice of the ice.

Territory Claims

Byrd’s comparatively large, well-resourced expeditions were a precursor of what was to come. After World War II first Australia, then many other countries including the two rising superpowers, the US and the Soviet Union, established bases on the Antarctic mainland.

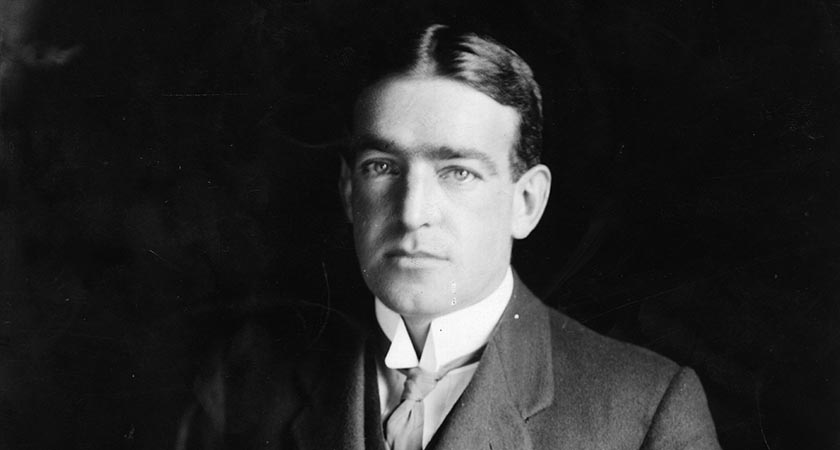

For the first time, numbers of national expeditions were present in Antarctica on a continuing basis, with parties living on their bases through the long, dark winter. Seven countries – Australia, New Zealand, France, Norway, the United Kingdom, Argentina and Chile – made claims to territory, three of which overlapped. With military personnel employed in some parties, it seemed possible that hostilities might break out between competing claims.

Antarctic Treaty

But that never happened, thanks to the miracle of the Antarctic Treaty, negotiated in the 1950s. Diplomacy found ways for the superpowers, the territorial claimants and other nations to agree to work together in spite of the differences.

A big part of that agreement was a clever arrangement over territorial claims, in which disruptive arguments over these claims were put on ice so to speak. The result is an Antarctica in which science, tourism, exploration and other endeavours can flourish even when nations involved have differences of view elsewhere.

So the history of Antarctica has become the story of how people live down there rather than how they get there. But the exploration never stopped. Where once it was men in ships and aircraft venturing into a world empty of humans, now it’s women and men exploring in a different way, looking at what Antarctica’s ice and snow, its atmosphere and surrounding seas, its mammals and birds and fish and myriad microscopic life forms can tell us about ourselves and our world. And instead of competing one against the other, they’re working together in a common cause.

Antarctica is the one place where it’s possible to forget the country on our passports and see ourselves as part of something bigger.

However, there’s still more to come in the history of Antarctica. The adventure hasn’t ended. It’s just different. In the magnificent desolation of Antarctica, we still feel nature’s power and majesty and mystery, as we always have. Except that now we also feel its vulnerability.

Chimu Adventures is a specialist in small ship expedition cruising. Contact us here for more information.

Talk to one of our experienced Destination Specialists to turn your Antarctic, Arctic and South American dream into a reality.

Contact us