How Argentina Became a Safe Haven for The Nazi

The link with Argentina and the Nazi Germany is something which has fascinated historians for decades. Here, we take a step back in time and revisit this complex chapter of the South American country’s fascinating history.

The 2015 discovery of a former Nazi lair hidden deep in the Argentinean jungle, reignited and refuelled curiosity into the mythical fables that have plagued South America ever since the end of WWII. Depending on whom you ask, or what you read, Hitler and his entourage managed to reach Patagonia in a doggy dinghy and spent the rest of their lives simultaneously hiding in the Andean wilderness and enjoying the blissful relaxation of a Patagonian ski resort town. Stories of cratefuls of Nazi gold washing up ashore along the coasts of Argentina and Brazil still persist, as does the search for ‘ratlines’, underground escape tunnels allegedly built by members of the Third Reich to avoid capture. Yet although some of the stories are a little far-fetched, others are actually real, their legitimacy proven by concrete evidence.

According to discoveries over the last few years, Nazi escapees made it further into the jungles of South America than previously thought. Although if you’ve never even heard of this not-so-secret link between Argentina and Nazi Germany, we should probably take it back a few decades…

From Nazi Germany to Argentina? Not nearly as far as you’d think!

The link between Argentina and Germany is not all that surprising, considering that German influence was well established throughout much of South America by the turn of the 20th century. The considerable influx of immigrants from not only Germany, but also Italy and Spain, ensured Argentina retain its long-held close ties with all three European countries. During the Second World War, and certainly with the rise of Nazi Germany, the link was something which was mutually nurtured. Germany promised Argentina trade deals and economic relations at the conclusion of the war, in return for its support.

Juan Domingo Peron, a celebrated lieutenant general who would later become Argentina’s President, was quite the outspoken Nazi sympathizer throughout much of his life. He even served in Mussolini’s Italian fascist army in the late 30s. Today it has become common knowledge that Peron personally oversaw the safe passage of hundreds (some say thousands) of SS members into Argentina towards the end of the war. This happened at about the same time that Argentina publically declared ‘war’ on Germany in March 1945. According to many historians, this declaration against the Axis Powers of WWII was a mere smokescreen to get undercover agents into Germany in order to help the now defeated Nazis to escape. Plus, the public display of support for the Allies no doubt helped Argentina’s relations with the US and Western Europe.

Peron’s role in the protection of Nazi war criminals wasn’t really confirmed until the late 1970s. The extent to which sympathizers went in order to aid them escape the Nuremberg Trials is still being uncovered today.

For fame, glory…or cold, hard cash

Many former members of the Nazi party found safe passage out of Germany through Italy and Spain, utilizing their looted Jewish funds, art and jewels to buy their way to freedom. Experts believe that at a time when the whole of Europe was plunging into economic disaster, the considerable monetary incentive would have even been enough to convince Allied officers to turn a blind eye and allow escapees to cross into ‘friendlier’ lands. From there, buying a spot aboard an Argentina-bound ship would not have been too difficult.

Argentina also benefitted from its newly acquired German diaspora. Almost all of the Nazis who made it across the ocean brought with them an incredible amount of wealth. They invested in Argentinian factories and aided local industries. Many worked for German-owned companies and almost all felt so supported in their new homeland, they didn’t even feel the need to hide their origins. Some, like Reinhard Kopps, are even attributed with starting neo-Nazi movements in their newly adopted countries.

The convergence of separate interests

Scholars contest that the main reason why so many Nazis managed to escape to Argentina, of all places, was because the separate interests of parties involved did make for a fortuitous convergence. For different reasons, both the Allies and Argentina felt it in their best interest to let these war criminals escape. So escape they did.

It is widely believed that the Allies – and the US in particular – were privy to this post-war mass-exodus from continental Europe to South America, and did nothing to prevent it. This was mostly due to the swift rise in Communism sympathizing in the very same countries which were actively seeking Nazi criminals to put on trial. The US had no interest in turning them over. At the same time, Peron was personally interested in having the ‘brains behind the Third Reich’ in his home turf. If his premonition of an imminent West VS USSR World War III turned out to be true, he wanted Argentina to be a key player and would have needed experienced military leaders on his side. The Third World War never came, luckily, yet Argentina kept its German officers nonetheless.

Yet Argentina wasn’t the only country to shelter Nazi fugitives. Peru, Chile, Paraguay and Brazil also became safe(ish) havens, but mostly only once Peron was ousted from power in 1955, rendering Argentina less than ideal. In the widespread anti-Peronist wave, many former Nazis feared they’d be hunted and promptly shipped back to Europe to face trial. Most dispersed to neighbouring countries and all finally adopted aliases and kept a low profile. Some were more successful at avoiding detection than others.

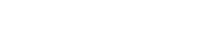

For a whole decade, Argentina was home to Adolf Eichmann, one of the key architects of the Holocaust and one of the most hunted fugitives in history. His covert capture by Israeli Mossad operatives on a Buenos Aires street in 1960, and his eventual trial in Israel, sparked a diplomatic row between the two countries. The row was eventually resolved, but Argentina still couldn’t halt Eichmann’s execution.

As time passed, and especially after the fall of Communism in Europe, the peaceful existence of so many Nazi war criminals became a hindrance to Argentina. The resurgence of the ‘Nazi hunters’ from the early 1990s led to the arrest, extradition and trial of many former German officers, most of whom were, by then, well into their twilight years.

In total, Peron is believed to have opened the Argentinian doors to more than 1,300 Nazis. The most prominent ‘enclave’ turned out to be Bariloche, a gorgeous Patagonian town renowned mostly for its superb skiing and mouth-watering chocolates.

It was here that the eyes of the world converged in 1994, when a US film-crew managed to track down and identify a former captain of the SS, Erich Priebke, and uncovered a long-held code of silence in the city. A local businessman who saw the potential for this link to be beneficial to the town’s tourism industry even compiled a Bariloche Nazi guide of sorts. Visit today and you can take a self-guided tour around town, mostly ogling a few homes which, once upon a time, belonged to former SS members-in-hiding.

A world away from the site of the crimes, the Nazi link in Bariloche, as in the rest of Argentina, seems utterly surreal. Most especially seven decades after the end of WWII.

For history lovers, Argentina is a powerhouse of exceptional interest. The fact it also boasts amazing landscapes, an excellent cuisine and a myriad of exciting activities is what makes it an immensely rewarding country to visit. So take a look at our extensive collection of Argentina tours and come discover this most enticing South American gem. Click here for more information.

Talk to one of our experienced Destination Specialists to turn your Antarctic, Arctic and South American dream into a reality.

Contact us